Mark Rossiter was deputy editor at the time of the Warrington Bombings 30 years ago.

He shares his memories of the day and the coverage that followed

Thirty years ago, before the rise of 24-hour internet news and mobile phones, Saturdays for a local weekly newspaper reporter usually meant having the day off. A time to relax.

Thursday’s Guardian was already on the news-stands, attention had switched to the following week’s midweek edition and emphasis was on pre-planned community activities and weekend sporting events.

Saturday, March 20, was a bright, fine day. The town centre was busy, shops were doing a brisk trade. Mothering Sunday was less than 24 hours away and in Bridge Street hundreds of people criss-crossed between stores in search of cards and gifts. For younger shoppers, gathered outside their favourite fast-food restaurant, it was a chance to meet friends and chat.

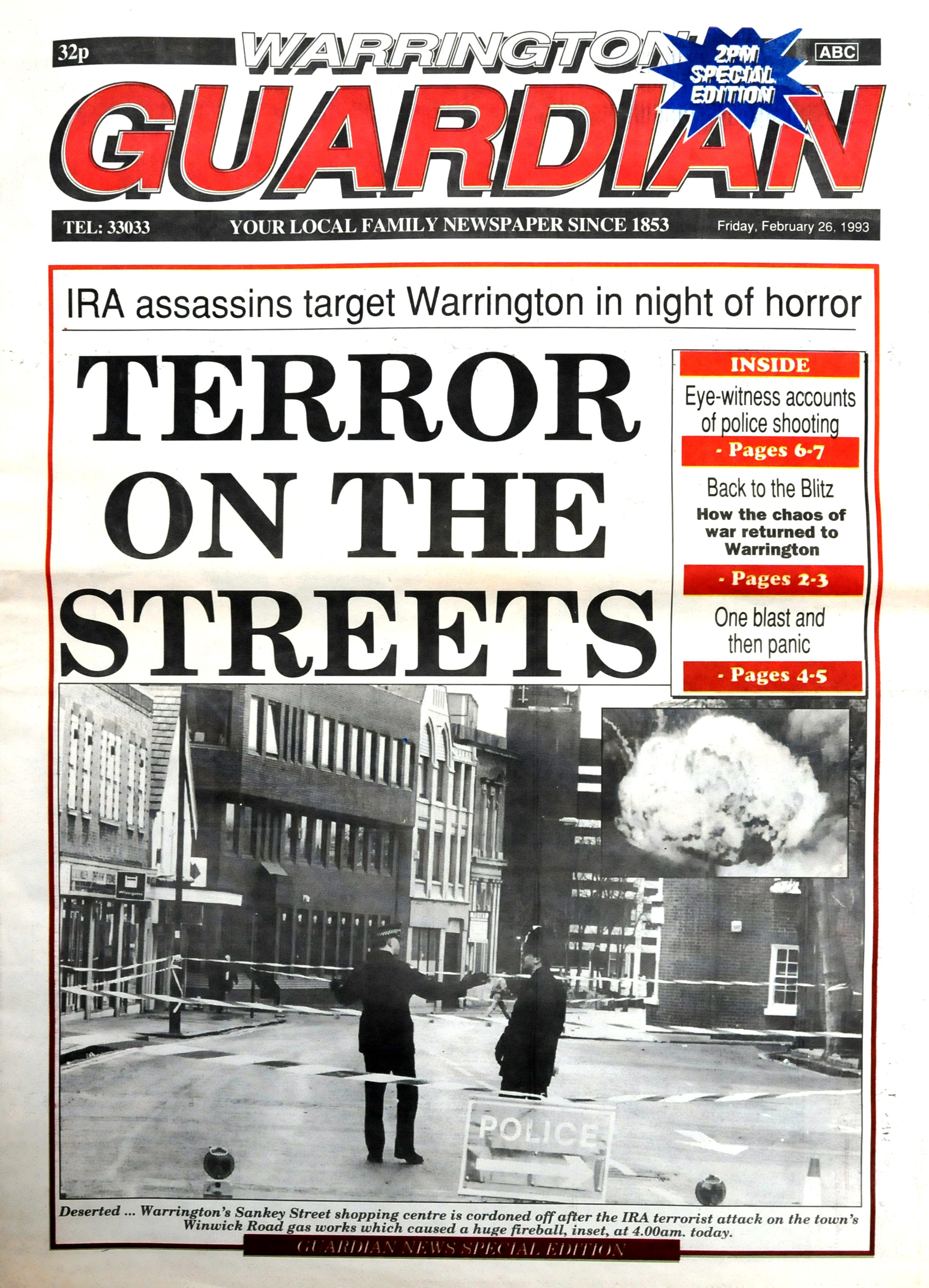

I was the paper’s deputy editor at the time and earlier that morning rumours of an IRA bomb threat were circulating - the intended target, Liverpool. The threat seemed plausible. Warrington had already been attacked three weeks earlier with the IRA detonating devices at the Winwick Street gas works. In the aftermath of that blast, boasts were made by the security services to reassure the public. A ‘ring of steel’ would be placed around Warrington to keep the terrorists out.

A special edition after the first attack

In hindsight, what better way for the IRA to demonstrate their credentials as a lethal guerrilla force and prove they could strike at will, than to target Warrington again, and this time with even more deadly effect.

What happened after the second bomb detonated outside McDonalds stays with me. I remember the courage of Guardian photographer Mike Boden who had been nearing Bridge Street when the second bomb detonated. It was his images that captured those terrible scenes. Mothers scooping up children and fleeing in panic, confusion, disbelief, the injured, the dead and the dying and, amid the screams, the bravery and kindness of those ordinary people tending to the fallen, none of them knowing whether there might be another blast just seconds away.

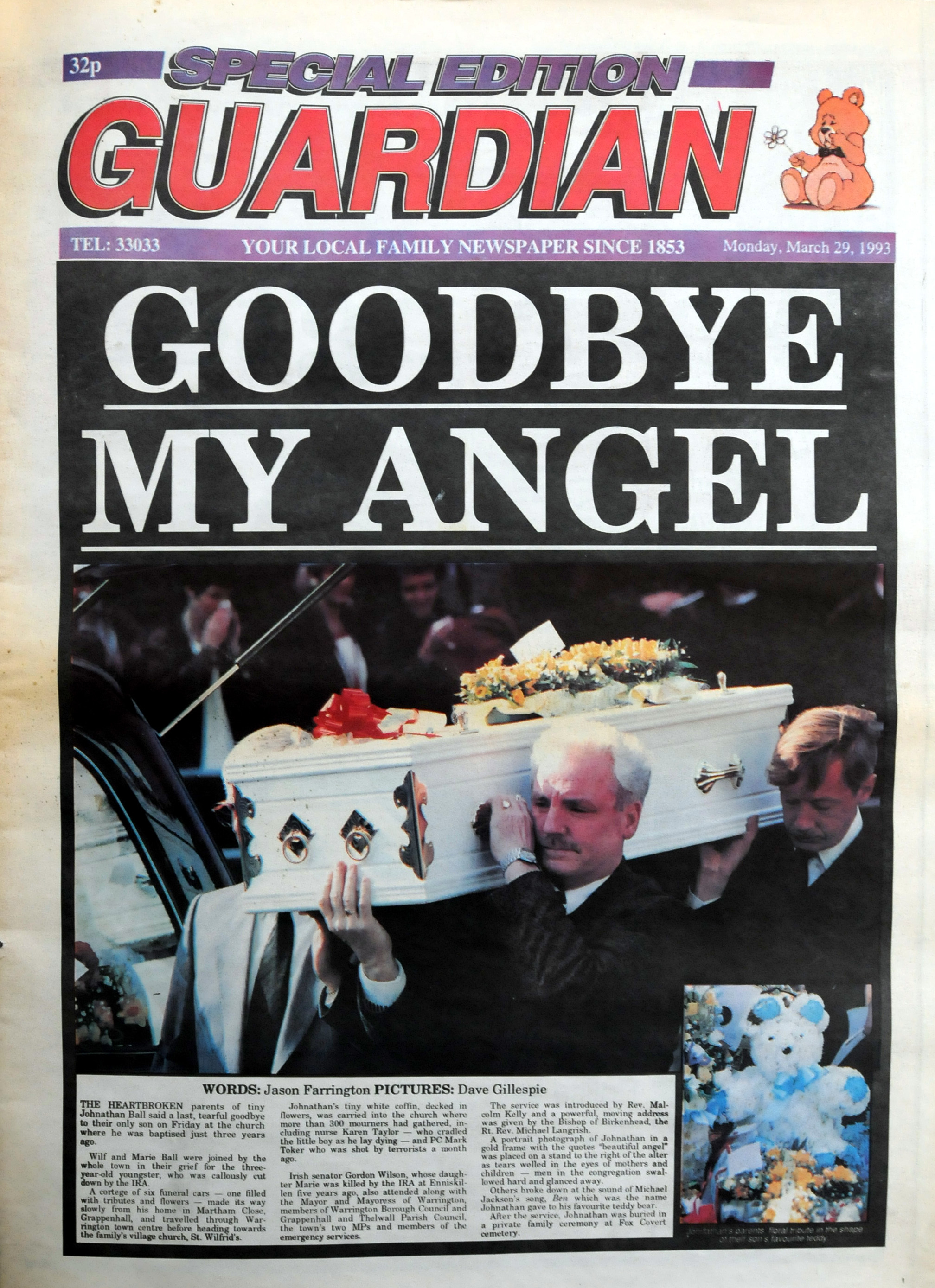

A front page after the funeral of Tim Parry

In 1993 the Guardian’s offices were at the foot of Bridge Street in the Warrington Academy building, a few hundred yards from the blast site. Mike and I met in the paper’s photographic dark room. This was the age of pre-digital cameras and camera phones. Developing before our eyes were the images that would go on to be featured on the front pages of newspapers and on television bulletins around the world.

Within half an hour a small team of Guardian reporters and photographers, some of whom had been in the town centre or had heard news of the bombs, had slipped between police cordons to reach the Guardian’s office. Most were young, poorly paid junior reporters with absolutely no experience of a news event of this magnitude. I still admire how none of them questioned their safety in a bid to do the job they did best, keeping residents and the wider world informed of what was happening in their hometown. All credit to them for heading towards danger as the town centre evacuated.

Inside the hour a Sky News broadcast truck had set up outside the Academy. Emergency service sirens blared. Traffic snaked away from the chaos. Police set up roadblocks and directed shoppers and workers away from the centre of town. Telephones rang constantly, news outlets from the UK and across the world clambering for information. The attention of some Sunday newspaper reporters, despatched from London and Manchester to secure exclusive photographs for their titles, was relentless. An insight into the world of the national press for our young journalists beginning their careers.

A special edition after the funeral of Johnathan Ball

The team set about doing what it could to gather information and reactions to what was unfolding, calling police and emergency services, hospitals, community organisations, civic leaders. Information was limited, restricted. The security services were being overwhelmed as families clambered for news of loved ones who’d been in the town centre.

What we did have were Mike’s images, photographs that spoke more than any words could, some so shocking that they have never been shared.

In the hours that followed we did the job we were trained to do. As a weekly newspaper we didn’t have the facility to print an emergency edition. We knew it would be Monday before we could share the words and pictures we had gathered with our audience. We also knew that this was a story that would not wait until Monday. The now defunct News of the World was the first newspaper to try and buy exclusive rights to the images we had. They were quickly followed by The Sun, Sunday Mirror and Sunday Times, Sky, ITV and BBC news channels. Freelance press agencies landed on our doorstep demanding to be seen. They knew the financial value of those pictures on the media market.

One of Mike Boden's images from Bridge Street

Inside two hours I’d been offered £30,000 for different images, around £60,000 in today’s money. As other media organisations from around the globe woke to the news, offers of cash continued. It was the start of a victims’ support fund that would swell to more than £300,000 and lead to the creation of the Warrington Peace Centre.

I’m proud to say that every single one of that small Guardian team remained until we’d exhausted and assembled all the information and details available to us that night, even when the office was plunged into darkness. Thankfully it was just a power cut but at that moment, the horrors of the day returned.

Decades later the Warrington bombing has been credited as a turning point in Anglo-Irish relations, the line in the sand which made those on conflicting sides of the troubles realise there could be a better way. If that is true, then the work of that young team of writers and photographers, who captured the images and words of victims and witnesses, with no thought of their own safety, should never be underestimated.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here