MOST on Merseyside will be familiar with the role and function of Wallasey Town Hall – Wirral’s administrative centre for local government, while others may know of the nearby Guinea Gap Leisure Centre.

But few people know these two River Mersey landmarks actually played a crucial, but little-known, role in Britain’s war efforts, as Tom Houghton reports.

The number of British soldiers killed or missing in action during the First World War is believed to have exceeded 700,000 – a statistic that devastated millions of families as sons, fathers, brothers and uncles went to fight and didn’t return home.

But the Great War that raged a century ago between 1914 and 1918 also produced an estimated 1.6m casualties for home-grown soldiers – from severed limbs to trench fever.

With a huge number of the injured returning to Blighty, domestic health services came under incredible strain – it is hard to imagine how our already heaving modern-day NHS would cope with millions more serious casualties, and work to identify and legislate for those hundreds of thousands of war dead.

Safe to say, it overwhelmed medical facilities both in the UK and at recently-established bases in France and Flanders. And while some military hospitals already existed, scores more were needed.

So in a bid to solve the problem, the government’s War Department set out to transform civilian hospitals and large buildings across the UK to military use, to treat and rehabilitate those hurt in warfare.

On Merseyside, Wallasey Town Hall was one of those chosen to fill that role in 1916.

According to a document recently published by Wirral Council called Wirral Town Halls and History, Wallasey Town Hall was a River Mersey landmark that had recently been built, with its foundation stone only having been laid by King George V two years before.

Costing over £150,000 and controversial in its appearance (the front of the building overlooking the river instead of Brighton Street) and Seacombe location (the new civic centre not in any way in the actual ‘centre’), it was to quickly transform into a facility providing care and support for injured soldiers. So much so that the agreement to use the building as a war hospital came even before the structure was complete.

Local history website History of Wallasey said it was built by Messrs Moss and Sons Ltd in the Renaissance style, later referred to as “one of the noblest buildings in the north” by a local newspaper of the time.

In terms of its function, Wallasey Town Hall Military Hospital was regarded as being a ward of the 1st Western General Hospital in Fazakerley.

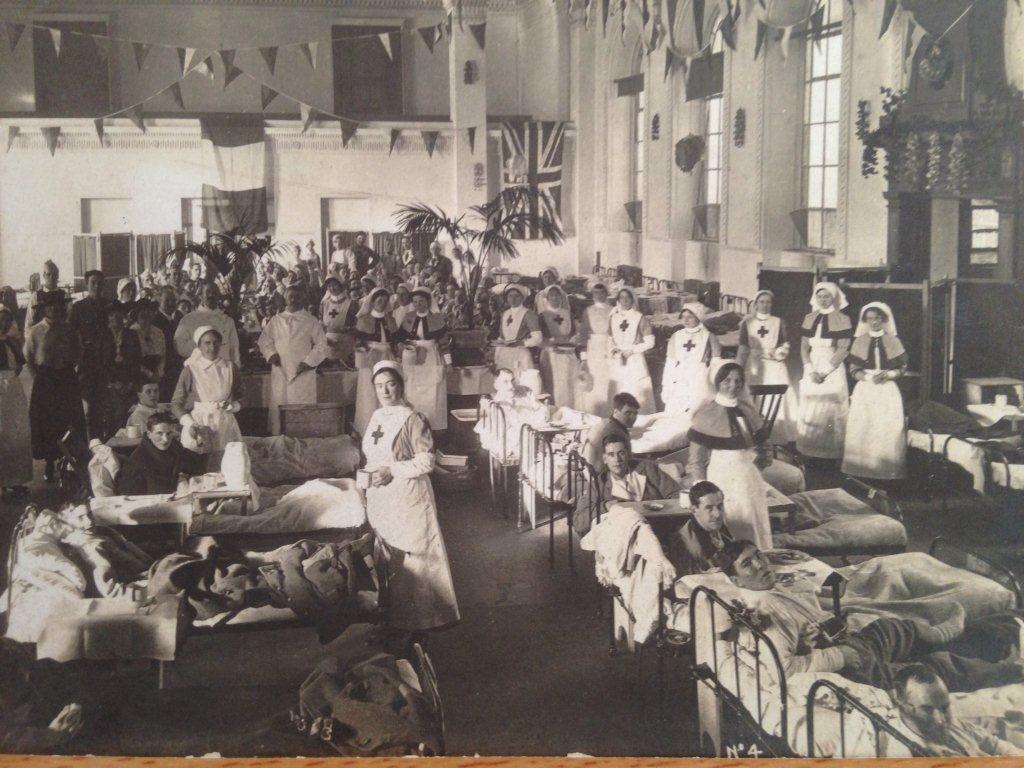

Work to convert it from its municipal use saw more than 400 hospital beds installed, with an estimated 3,500 casualties treated there – although other estimates claim the figure was closer to 6,500.

Guinea Gap Swimming Baths, just a stone’s throw to the south, was used for hydrotherapy and recuperative exercise for the injured.

Inside the town hall, rooms today used for committee meetings and workshops and classes were lined wall to wall with beds that were for the majority of the period all taken by soldiers from Wallasey, Wirral and the wider North West region.

With Liverpool and the Mersey well-connected by both rail and sea, Wallasey was a convenient first stop for many arriving into the country who would then need to make onward journeys further afield. If required, they would also take shelter at the hospital.

Not a great deal is known about how the facility was managed aside from directions being given by the War Department, although there are several interesting insights available, and various images.

An excerpt from the Wallasey News, revealed in Stephen McGreal’s book Wirral in the Great War, described the scene inside the hospital one Christmas.

It said: “The wards were very tastefully decorated and the patients regaled with seasonal fare through the generous help afforded the committee who have so long undertaken the good work of providing extra comforts for the wounded.

“While the Christmas dinner was in progress the hospital was visited by the mayor and mayoress. In the evening there was a fancy dress carnival followed by a whist drive.”

Another tale in Mr McGreal’s book revealed how in 1916, funds were needed to buy a new ambulance, as the town only had one, with its trailer required for local needs.

So a public meeting was held on August 16 with the aim of raising £1,000 to buy three ambulances. Almost all of that amount was raised in just eight days, with an unexpected boost from a Wallasey man stationed in New York helping the fund reach £1,400 in ten weeks.

Mr McGreal’s book added: “The vehicles would greatly alleviate the pressure during the transportation of wounded from [Birkenhead] Woodside station.”

With soldiers able to rest and recuperate and not much more, some took to writing, and the following poems have been found in the council’s archive.

The first, called United We Stand, appeared to encourage a sense of positivity and optimism among the wounded soldiers.

United We Stand

Learn to know as you jog along,

The value of a smile,

A glint of sunlight on your face,

Just as you meet the while,

It speaks a message of its own,

To stranger and to friend,

So wear a smile and pass it on,

T’will pay you in the end.

Rifleman PW Merritt. The Rangers. Written January 10, 1917.

A second by a wounded gunner from the Royal Garrison Artillery aired his views on Wallasey:

To: ‘the disturber of our peaceful dreams’

Through foreign lands I’ve wandered and many strange places I have seen,

But I think the strangest of them all is this place called ‘Wallasey’,

I don’t write this in fancy nor do I write it for fame,

But I do wish to be remembered – so I will sign my name.

Gunner Jack Whitton. Royal Garrison Artillery. Written November 21, 1916.

As the conflict raged on, demand for hospital beds rose, and one of the war department’s actions in the later years saw more buildings turn to military use, as well as private buildings such as large houses.

A framed paper scroll of thanksgiving from the government to those involved in running the war hospital, and held by the Imperial War Museum, said: “The army/council in the name of the nation thank those who have rendered it this valuable and patriotic assistance in the hour of its emergency and they desire also to express their deep appreciation of the whole-hearted attention which the staff of this hospital gave to the patients who were under their care.”

It was written after the war concluded, and added: “The war has once again called upon the devotion and self-sacrifice of British men and women and the nation will remember with pride and gratitude their willing and inestimable service plaque.”

All of that meant the town hall, awaited for years by the Seacombe community, could not be accessed by the public until after 1919.

That was when they had their first real look inside the offices – marvelling at the 180-ft tower and elaborate statues.

It’s believe the building was once again available for civic use two years after the end of the war – in November 1920.

Its role in wars didn’t end there, sadly. In 1940, during the Second World War, it was hit by a bomb – and a treasured organ bought in 1926 was totally destroyed.

The 1960s saw the building of the South Annexe to create more office space, for what was believed to be a cost of £130,000.

In 2015, a plaque was erected at the town hall in memory of all staff and people of Wallasey who helped the injured soldiers at the military hospital.

Today, it houses Wirral Council staff, and is the location of dozens of meetings every month, as well as hosting weddings, function rooms and a One Stop Shop.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel