THE 220-year-old story of Jack Crawford, the hero of Camperdown, has such an enduring appeal that his brave deeds were used as part of the campaign for his home city of Sunderland to be named City of Culture in 2021.

A bronze statue dedicated to him still stands in Mowbray Park, as recently as 2013, a documentary was made about him, and city councillors are promoting his amazing feat ahead of the visit of the Tall Ships Race next year.

But who was he, and what did he do to deserve such legendary status?

Crawford was born in Sunderland’s East End on March 22, 1775, and became a keelman aged just 11, ferrying coal on the River Wear.

Press ganged into the Royal Navy in 1796, he served on the gun ship HMS Venerable under Admiral Adam Duncan, the Royal Navy Commander-in-Chief of the North Seas.

In 1797, Britain was at war with France, Holland and Spain and, at 12.30pm on October 11, the British and Dutch navies met in battle off the coast of Norway, near Camperdown, close to Bergen.

Instead of forming a line of ships, Admiral Duncan split the British fleet into

two groups, which broke through the Dutch ships, firing damaging broadsides.

It was a daring move, but successful, as it prevented the Dutch fleet from joining the French Navy and scuppered their plans to invade Ireland and then to attack Britain.

By 3pm, 203 British sailors were dead and 622 wounded; 540 Dutchmen were dead and 620 wounded. Britain had captured 11 enemy ships, but they were so badly battered they were useless.

Four more were sunk, but the British themselves were so damaged they were unable to pursue the remaining ten ships as, defeated, they returned to port.

Various British admirals and captains were honoured, but the popular "hero of Camperdown" was Crawford.

During the fierce fighting, HMS Venerable's main mast, bearing its colours was felled.

Its loss could have been interpreted as surrender.

But, under heavy fire, 22-year-old Crawford climbed what was left of the mast and nailed his admiral's colours to the top, leading to victory for the British, and forever entering a phrase into the English language.

After the battle he was hailed a hero and was honoured at a great victory procession in London.

In March 1798, the people of Sunderland presented him with a silver medal and in January 1806, Crawford was formally presented to King George III and granted a pension of £30 a year.

But once back on dry land, he fell on hard times, turning to the bottle. He sold his medal to pay for his drinking and died, aged 56, in 1831, the second victim of a cholera epidemic that started in Sunderland and swept the country. He didn't get a headstone until 1888.

Outside of Sunderland, some historians have cast doubts on just how heroic he really was, claiming he was drunk on deck during the battle and had to be forced to climb the mast. Really, they said, he should have been court martialled for disobeying orders.

And in 1999, an American author had to apologise after dismissing Crawford as a fraud, sparking outrage in the region.

Sheri Holman depicted Crawford as a hapless wretch who was bullied into climbing the mast by his crewmates.

Then-Sunderland City Council leader Colin Anderson, an amateur naval historian, described it as a "disgraceful slur on a brave young man this city is justifiably very proud of".

Mrs Holman said: "I had no idea he meant such a great deal to the people of Sunderland and Great Britain. All I can say is that I am very sorry and that I wrote the passage with the best intentions."

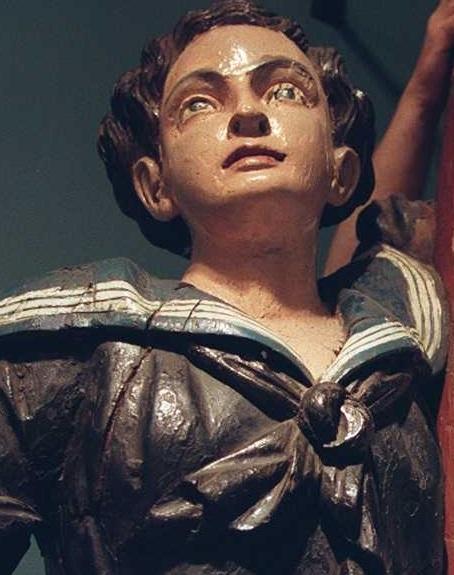

Crawford's monument was erected in Mowbray Park in 1890, and was unveiled by the Earl of Camperdown, the grandson of Admiral Duncan – and it is believed the colours Crawford nailed to the mast were displayed at the ceremony.

“And, as far as we are aware, they have never been seen again,” says Michelle Daurat, project director for The Tall Ships Races Sunderland 2018. “We believe the time has come to find them.”

Up to 80 Tall Ships will be in the port from July 11 to 14. Michelle adds: "[They are] very similar indeed to the sort of ships on which Jack served during his time at sea.

“He died in poverty and his heroic actions – which turned the tide of war – have largely been forgotten. But we want to change that and I can’t think of a better tribute to him or to the huge role played by this city to the nation’s maritime heritage, than to return the colours to Wearside.

“If anyone, anywhere can help us track down the colours Jack nailed to the mast we desperately want to hear from them.”

*Anyone who can shed light on the whereabouts of the colours is asked to call 0191 2656111

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here